-40%

WWI USMC Lanyard (“PAT. FEB.-20-17”) for M1917 Revolver M1911 ACP Mint NOS!!!

$ 73.91

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

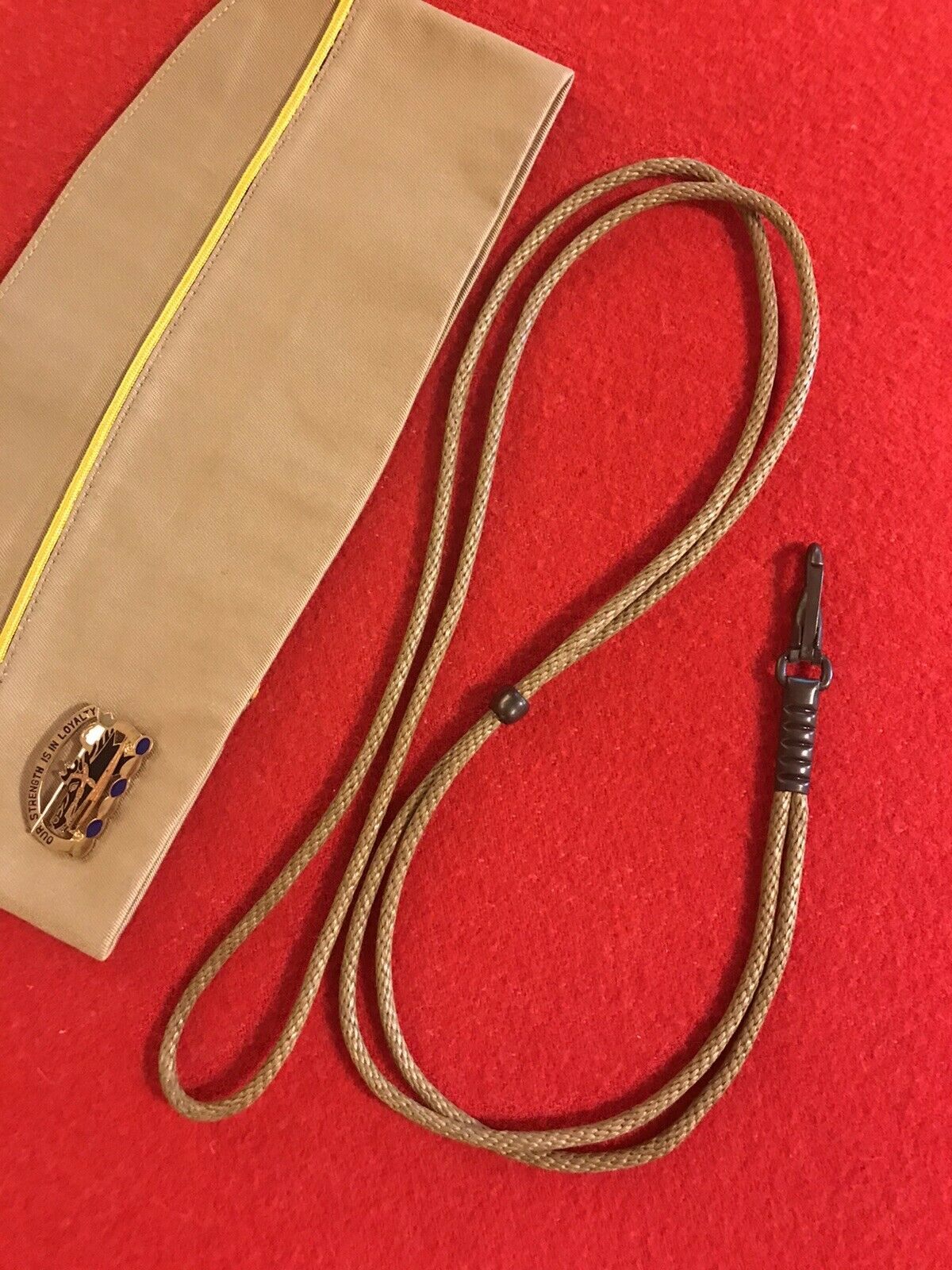

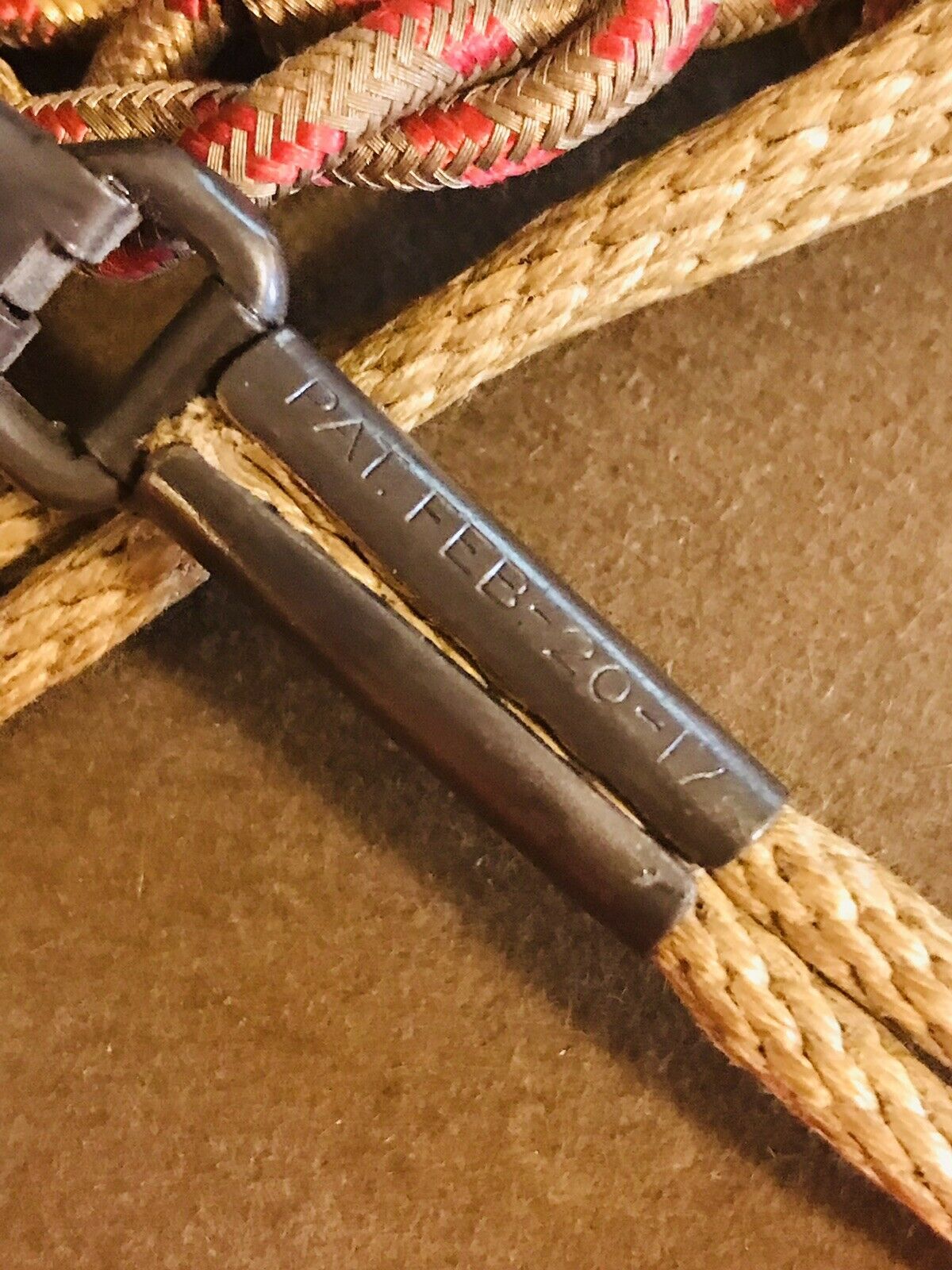

WWI (and WWII) USMC and Army Pistol LANYARD (“PAT. FEB.-20-17”

) for the M1917 Revolver and M1911 .45 ACP.

Mint NOS Unissued!!!

NOTE

: Since the Leather-finished WWII model LANYARD with the open Steel-wire hook (made only by ‘

HICKOK

’ and only in ‘

1943

’ — and so marked and dated) was not available for the first two years of the Second World War, this WWI Lanyard was paired with the sidearms in the early campaigns!

- This is an

UNTOUCHED

ORIGINAL!!

- There is absolutely

ZERO

wear to the

BLACKENED

FINISH

of the crimped

BRASS FITTING

which is crisply stamped

(

“PAT. FEB.-20-17”

)

; the small

SNAP HOOK

; and

ADJUSTABLE

“

SLIDER

”!!

- The lightly waxed

POLISHED BRAIDED 3/16” CORD

is in absolutely

PERFECT

condition! The Light Shade OD#3 Cord is

STILL

STIFF

!

-

ZERO

abrasions, stains, "fuzzed," or any sign of wear whatsoever!

These attached to either:

(1) the

SWIVEL RING

on the Frame of the

M1917

Revolver

,

(2) the

LOOP

on the base of the

Early M1911 MAGAZINE

,

(3) the Later

LOOP

on the

M1911A1

Frame below the Grip.

This

LANYARD

was worn by

OFFICERS, NCOs,

personnel with crew-served weapons,…and especially

MOUNTED

TROOPS

…such as the

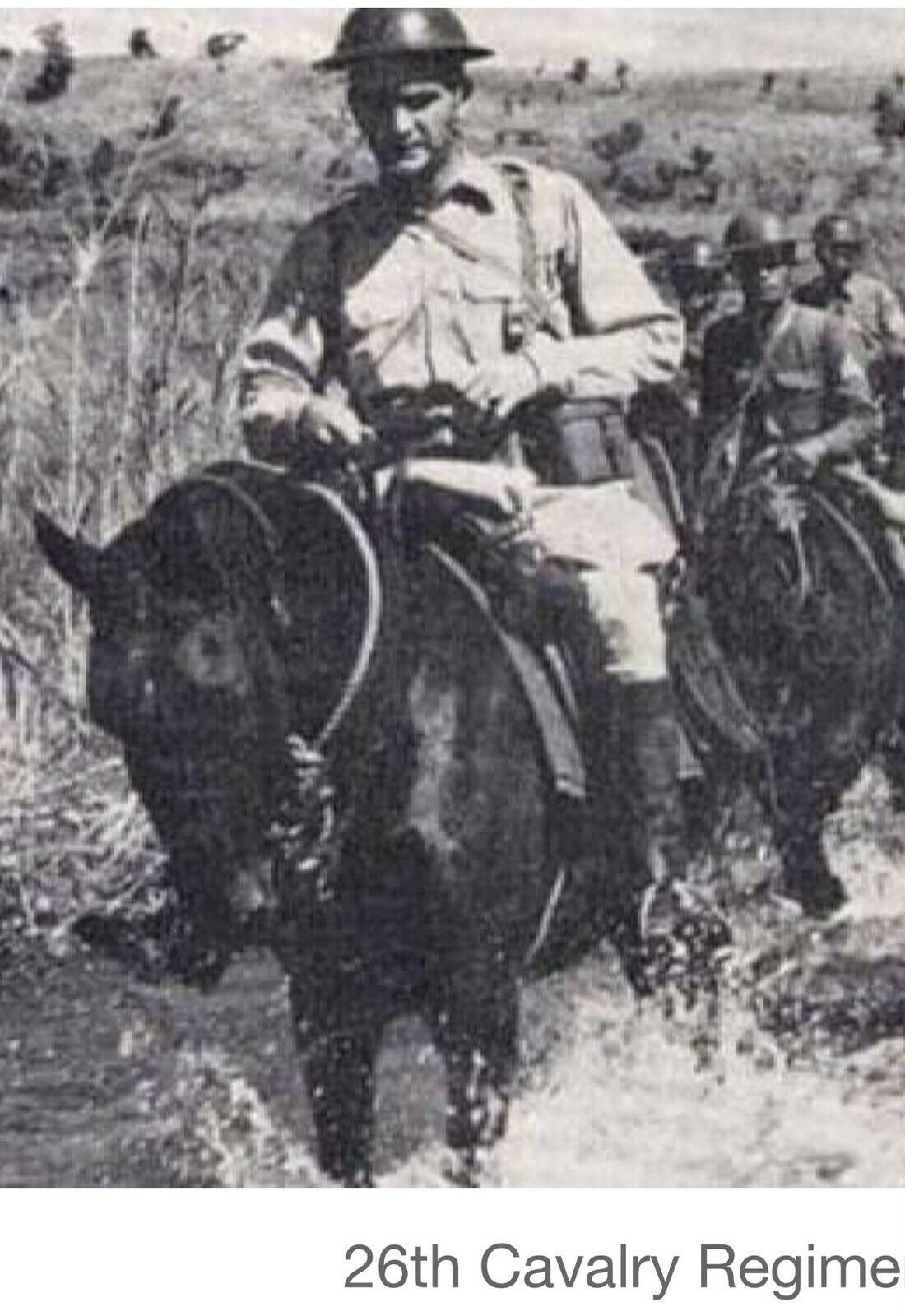

26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scout), Regular Army.

The final

U.S. Cavalry

charge took place in the Philippines on 16 January 1942, when the

LANYARDED

pistol-wielding horsemen of the 26th Cavalry Regiment

(Philippine Scout)

repulsed a tank-supported Japanese attack!

*****

During the delaying action the

26th provided the "stoutest" and only "serious opposition" to the Japanese; t

he majority of the units sent north towards the Lingayen Gulf were divisions (11th, 21st, 71st, & 91st Infantry Divisions) of the untrained and poorly equipped Philippine Army. For instance,

during the initial landings the regiment alone delayed the advance of four enemy infantry regiments for six hours at Damortis, and on 24 December repulsed a tank assault at Binalonan.

However, the resistance was not without cost, as by the end of 24 December the regiment had been reduced to 450 men. Following these events, the regiment was pulled off the line and brought back up to a strength of 657 men, who in January 1942 held open the roadways to the

Bataan Peninsula

allowing other units to prepare for their stand there.

Bataan

The

26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scout)

consisting mostly of Philippine Scouts, was the last U.S. cavalry regiment to engage in horse-mounted warfare. When

Troop G

encountered Japanese forces at the village of

Morong

on

16 January 1942, Lieutenant Edwin P. Ramsey

ordered the last cavalry charge in American history. It would not be until 22 October 2001, when American Soldiers would enter combat on horseback again, when members of the 12-man

Operational Detachment Alpha 595 (Green Berets),

accompanying members of the Afghanistan Northern Alliance, rode into battle at Cōbaki in Balkh Province.

****

26th Cavalry Regiment

As Ramsay recalled in his autobiography,

Lieutenant Ramsay’s War: From Horse Soldier to Guerrilla Commander (Memories of War),

his orders were to lead 27 other cavalrymen on horseback to the strategic coastal village of Morong to delay Japanese forces from marching toward Bataan. “I now knew the coastal road by heart, and despised it,” Ramsey wrote. “It was scarcely more than a jungle track, deep rutted and thick with dry-season dust, a gray powder that irritated the eyes, clogged the nostrils, and coated the throat. The underbrush tangled up closely on either side, so dense that one could not see three feet within it. It was a dark, dangerous place, virtually an invitation to an ambush.”

Ramsay entered the village just as a Japanese advanced guard had crossed a river to reach the village center’s Catholic church, the only stone structure in the vicinity. Gunfire immediately erupted, and

the only way for Ramsay’s men to break out against the larger Japanese force, which was supported by tanks, was to order a desperate cavalry charge.

“I brought my arm down and yelled to my men to charge,” Ramsay wrote in his book. “Bent nearly prone across the horses’ necks, we flung ourselves at the Japanese advance, pistols firing full into their startled faces. A few returned fire, but most fled in confusion, some wading back into the river, others running madly for the swamps. To them we must have seemed a vision from another century, wild-eyed horses pounding headlong; cheering, whopping men firing from the saddles.”